WWW.HAUSSITE.NET

Spuren der Inszenierung

04 / 11 / 01 - 14 / 12 / 01

Exhibition

Spuren der Inszenierung (Traces of a Staging )

curated by Constanze Ruhm

Harun Farocki, Olaf Metzel, Wendelien van Oldenborgh

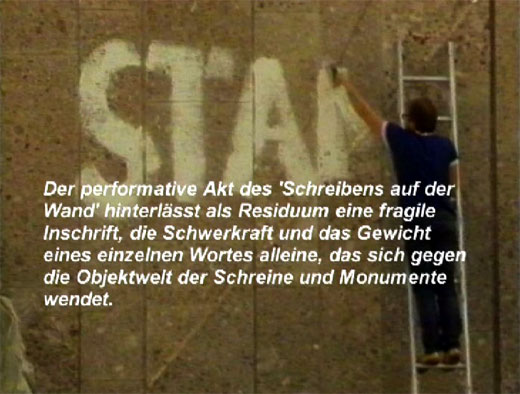

Olaf Metzel installing in 1984 Württembergischer Kunstverein

(2002 -new image/title montage for this exhibition)

The exhibition introduces three specific moments extracted from a sense of contemporary public spaces, and sets these in relation to various possible forms of occupation, inhabitation and demarcation. The spaces' borders and margins are usually defined by contemporary surveillance systems recording fragmentary gestures, unpredictable movements of bodies, evocations of past and future potential transgressions that transform into materials for artistic investigation.

Each work contains aspects of performance, deals with issues of observation and surveillance, as well as with the notion of the system of architecture as embodiment of institutional strategies of constraint, thus defining and limiting the subject's potential sphere of influence. An interruption within the system's economy occurs in a moment of exchange constituting a punctuation mark in space, in which a subversive potential is finally released.

The Prison:

Harun Farocki

Ich

glaubte Gefangene zu sehen (2000)

Die Maschinen tun ihre Arbeit nicht länger blind (2001)

Harun Farocki: (top image) 4th floor, haus.0 Video- and Print Plug-ins with

DVD Farocki collection and set of 1970s / 80s Filmkritik journals,

(ed. Harun Farocki) (below images) installation views, 2nd floor

"Images from the maximum security prison in Corcoran, California. The surveillance camera shows a pie shaped section of a concrete courtyard where the prisoners are allowed to spend about half an hour a day in shorts and usually shirtless. One prisoner attacks another whereupon those who are not involved immediately lie flat on the ground, arms folded over their heads. They know what is going to happen: the guard will call out a warning and then fire rubber bullets. If the prisoners do not stop fighting by then the guard will fire with real ammunition. The images are mute, the gunsmoke from the shot drifts through the frame. Camera and gun are right next to each other thus conflating the field of vision with the field of fire. The prisoners are almost naked (they constantly work out) and all they have left is their clan affiliation." (Harun Farocki)

Over time and only recently, director Harun Farocki’s work has gradually shifted from the film frame into actual space and architecture. It has been developing along spatial terms, which was in part possible due to his analysis of montage and use of various media sources. His installation works are directly linked to the language of his media practice while matching architectural space to issues of control and surveillance. This is exemplified in his well-known second installation Ich glaubte Gefangene zu sehen (2000), shown here in single channel format. The title Ich glaubte Gefangene zu sehen (I thought I was seeing prisoners) refers to a line uttered by the character of Irene in Roberto Rossellini's Europa 51. When she sees workers leaving a factory she says, "I thought I was seeing convicts."

This installation is joined by a new work presented for the first time Die Maschinen tun ihre Arbeit nicht länger blind, which was developed by Farocki in relation to the specific outline of the project.

The new work can be described as a representational interplay, a breakdown of Farocki's recent investigations that link with his new work on intelligent machines, intelligent weapons and how these mutually advertise each other.(H.F.) Seen together, the shift from a society of discipline towards a society of control is a constituent factor within Farocki's work and thus emphasized as a line of thought along which both installations develop. Farocki writes: "The images produced by a surveillance camera could be called operative, as well as these of production control and material testing. It's just fine to call a testing that is operated through sensors 'damage free': gazes don't destroy anything."

The Museum:

Olaf Metzel

Stammheim Dokumente (1984/2001)

7 Animated scenes - Olaf Metzel, Stammheim documentation

from video produced for exhibition

Olaf Metzel’s Stammheim sculpture was installed in the public courtyard of the Württembergische Kunstverein in 1984, in the aftermath of the Stammheim Trials involving members of the Rote Armee Fraktion, who when found guilty were placed in Stuttgart within a custom-built, new type of maximum-security prison. By the time of Metzel’s invitation for a public sculpture, RAF members Ulrike Meinhof, Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and Jan Carl Raspe had committed suicide in prison (or, according to a large number of supporters, had been killed), and further trials against Christian Klar and Brigitte Mohnhaupt were impending.

The conflicts between the RAF and state together left traces engraved in German society's collective memory, raising issues such as control. There was parallel an expression of processes transforming the fabric of representational politics and culture, registered through a generation by their destabilization of cultural norms, conventions and attendant values that operated in the restorative postwar climate. History itself returned as an ongoing conflict in the contemporary reality, demanding if not empowering the reformulation of a engaged, politicized subject.

Metzel’s Stammheim sculpture reflects on the transition into the mid 80s Germany. It consists of a three-meter high wreath leaning on a wall that displays the word STAMMHEIM in white graffiti letters. The wreath is cast from concrete, an industrial material contradicting conventional memorial materials like bronze or marble; a material belonging to the language of building and architecture, the autobahn view of Germany’s satellite cities and freeways, vernacular metaphors burdened with history. Next to this concrete manifestation of German reality are large, painted white letters spelling out the word Stammheim in an individual's single gesture: a word which is charged with all different kinds of ominous connotations. The simple graffiti undermines the conventions that official rites of recollection want to establish.

Metzel's work is a non-memorial, it does not inscribe the names of people to a historical moment, but instead the name of one city institution and architecture onto another. Through its placement in the precariously defined public space, the artwork suggests joining two different spaces – the prison, the ‘museum’ - by a sudden act, an individual’s spontaneous gesture. He has always implied that it should not be understood as a memorial but a public sculpture. Its character suggests to present in the language of art a finished state of formal balance and resolution, but as the agency through which to perceive a very identifiable unresolvedness - that in the public itself, as a body politic, of which the artist is one. The gesture itself was considered a spontaneous performative action, the rendering of a - in Metzel's words - "synthetic fragment" which included history and recollection as part of the material.[1]

installation view, Künstlerhaus Stuttgart

The performative act of 'writing on a wall' leaves as a trace a fragile inscription, the gravity of a single word alone set against the object world of shrines and monuments. In a way, an act of erasing might render the letters more visible: emphasizing the gravity of something that is weightless, a name only, a montage of different and invisible materials. Today it still seems sometimes as if the letters had materialized by themselves over night and will keep doing so even after removal, the repressed that always returns leaving behind a trace, a single word

The Stadium:

Wendelien van Oldenborgh

Itīs

full of holes, itīs full of holes (1999/2001)

"Your body is a boat to lay aside when you reach the far shore.

Or sell it if you can find a fool, itīs full of holes, itīs

full of holes."

William Burroughs, The Western Land

installation view, "It's full of holes. It's full of holes", Künstlerhaus

Stuttgart

The scene represented in the double slide projection deals with the crucial moment in which a specific kind of contact between individuals is established, within which a notion of physical intimacy transgresses the conventions defined for regular public spaces and social spheres, thus hinting to the possibility of a certain loss of control.

A female

police officer searches the bodies of women at the entrance to a stadium

where a football match will soon take place. The stadium represents a contemporary

place of ritual violence and the loss of control. The female police officer

incorporates the law, thus indicating the limits of acceptable behavior.

She symbolizes the line one should under no circumstance cross. Though the

way she touches the women' s bodies, most intimately, sexually charged,

lingering between transgression, aggression and embrace, suggests she herself

will potentially ignore the demarcations and borders of convention. Her

slight and professional movements verge at the erotic, the framing of the

camera sometimes suggests a forced intimacy between police officer and the

women under investigation. There is only a marginal hint as to where this

takes place, a small indication of the location in the form of a small sign

attached to the metal chain that separates the line of waiting women from

the surroundings. The sign says: Nord Esplanade. It remains unclear

where this Nord Esplanadeis located, and it does not matter since

it could be anywhere, or even the title of a follow up to this work.

The scene was shot on super-8 film of which single frames have been transferred to slide and enlarged. They pass by the eye of the spectator in slow motion, a procession of frames dissolving in the semi darkness of space, always leaving behind a trace, a memory of their predecessors. The silent black and white images sometimes recall the early days of cinema. We become witnesses to a soundless carnival being recorded through van Oldenborgh's subjective perspective. She patiently and without commentary watches what is going on. In fact, we do not need neither subtitles nor a voice over: since we are able to quickly decode the language of social hierarchy, of the erotic, of power and control all condensed within a brief moment, an evanescent flickering image as if someone's memory had been clandestinely recorded. Fragmentation and isolation of singular entities, of 'reality frames', the line of separation between society and its laws are the topics of van Oldenborgh's work. She allows us to glimpse a moment of the symbolic violence pertaining to contemporary rites and rituals. Over time, through repetition and isolation, the small events the artist records become larger than life: one could call them "ritual molecules" unveiling the structure of our minds as well as collective subconscious. " It is a research on the secret ties and connections that are dictated by shame and seduction - the rules that reason does not know of - between body and language, between the physical and the mental. It is precisely through such gaps, actual "holes" within our conception and knowledge of the world, that the artist traces the mechanisms of unconscious projections that our habitual fears bring into play." [2]

These installations raise issues of potentially different kinds of models of the observer always connected to shifting vantagepoints in a world of flows, charts and nets. The artists and their works figure as interfaces between the subjective and objective, between observer and observed, thus focusing on the impact of performative, transgressive acts as a potential third point, as either staged or perceived within the framework of art practice. They employ the principle of montage in order to recombine synthetic fragments of the real, the recollected, and the technological. Farocki replaces the observer with the seemingly 'objective' gaze of surveillance cameras that just record that what happens with the notorious lethal innocence technology only can claim. Metzel touches on issues of a gesture in relation to a society's capability, the necessity of remembering. Van Oldenburgh's work employs the notion of a radically subjective artist's perspective located within a public spectacle of control and transgression. All works frame events that oscillate between the archaic and the mundane, metaphors rendering visible the violence of institutional constraints imposed onto the subject through real and virtual architectures as well.

How surveillance and spectacle relate to each other is being explored within this specific configuration of works. Architectures both real and virtual are introduced and investigated: as means of control and constraint, thus exemplifying what Foucault has described as the process of transformation from a society of discipline to a society of control. The narrative these works constitute in relation to one another can be read more in spatial terms, as opposed to the indexical arrangement of materials on the fourth floor. It is not only telling of architecture and subject, but touching on the notion of the meaning of entrances, walls and interiors, gaps and holes, that what elapses in the fabric of social contracts between individuals and the state's institutions. The act of performance constitutes a pivotal moment defining the relation between observer, spectacle and institutions. It can be read as a closure, a resolution to the unresolved, but at the same time, it depends on who defines what isthe performance, what isthe spectacle.

The body politics of a society understood as the people of a nation, or the nation itself considered as political entity with the state as control factor, is framed in each work within a singular, silent, transient gesture of either an apparatus or that which adverses it. Strategies bordering on the ritual, exercises completed under constraint, rendering clearly the borders within and outside of architectural representation of power: the stadium, the prison, the museum. Each work brings to the fore these issues of body politics understood as a fundamental, constituting moment of a society's construction.

The 'writing on the wall' is a foreboding hint, spell, act of recollection and a fading memory. It speaks of omissions, of sudden disappearances, of the subjects of a society and their transgressive practices, the violence of desires and the temptation of forms.

Text, Translations: C.R.

[1] "Then I was writing this word - a completely spontaneous moment, a synthetic fragment, since the letters are not made from bronze..." (Interview Olaf Metzel with Ursula Frohne, 1985) [2] From a text by Thomas Kocek, 1999.